As we head into the presidential election season, the United States is confronting several significant challenges that are likely to inform much of the political debate in the coming months:

As we head into the presidential election season, the United States is confronting several significant challenges that are likely to inform much of the political debate in the coming months:

Globalization, rapid technological change, large demographic shifts, and accelerating environmental deterioration all contribute to these complex, systemic problems. For example, unfair trade practices, offshoring, currency manipulation and technological advances have contributed to the decline of American manufacturing since the late 1970s—especially after 2000—costing millions of skilled, middle-income jobs. Not only has this fueled stagnating incomes and rising inequality, it has shrunk middle-class job opportunities for workers without adequate skills or training, especially in low-income urban and rural communities—fostering growing disaffection, unrest, and protest around the nation (e.g., Ferguson, MO; Baltimore, MD).

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that perceived adverse economic impacts generate political resistance to policies designed to address climate change concerns. For example, U.S. regions most hurt by reduced reliance on the use of coal have long histories of economic distress—including the loss of manufacturing—and the most affected jobs tend to be more middle-wage and unionized than new “clean” energy jobs, created, for example, by solar and wind power. In contrast, jobs in the fossil fuel sector, especially in the growing unconventional energy sector (shale gas and tight oil), tend to be in high demand, highly skilled and well paid. Development in this sector in fact has strengthened economic growth in several U.S. regions.

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that perceived adverse economic impacts generate political resistance to policies designed to address climate change concerns. For example, U.S. regions most hurt by reduced reliance on the use of coal have long histories of economic distress—including the loss of manufacturing—and the most affected jobs tend to be more middle-wage and unionized than new “clean” energy jobs, created, for example, by solar and wind power. In contrast, jobs in the fossil fuel sector, especially in the growing unconventional energy sector (shale gas and tight oil), tend to be in high demand, highly skilled and well paid. Development in this sector in fact has strengthened economic growth in several U.S. regions.

Internationally, the challenges of economic inequality, climate change and national security also are linked. A 2014 Pentagon report asserts that climate change poses an immediate threat to national security, with increased risks from terrorism, infectious disease, global poverty and food shortages. Yet, even though climate change is likely to have its greatest impacts on the world’s poorest regions, many developing nations resist cutting back their use of fossil fuels, which they see as critical to their economic development and ability to reduce poverty. At the same time, the dependency on oil and natural gas resources factor deeply into the economic and political instability of the Middle East, and other parts of the world (e.g., Ukraine and the South China Sea). Indeed, widespread poverty and large-scale youth unemployment in many Middle Eastern countries and other poor oil-dependent nations feeds into radical insurgencies that foster global terrorism.

While we recognize the inherent difficulties in tackling these challenges, we believe smart, “high road” policies, strategies and actions can move us towards successful solutions that are systemic, integrative, adaptive, resilient and equitable. Taking the “high road,” means merging diverse, sometimes competing interests into broad solutions that meet medium-to-long-term objectives. Effective policy solutions ensure that all affected stakeholders—from the private sector, civil society and government—are at the table. In contrast, “low-road” approaches emphasize narrow, short-term objectives that benefit only a small set of interests and stakeholders, often at the expense of others. Indeed, following the “low road” increases differences between groups and creates “vicious circles” that make it harder to find genuine, sustainable, long-term solutions that create widely shared economic prosperity.

In general, sustainable strategies encompass four elements:

Upcoming issues of this newsletter will feature articles that explore high road approaches to different aspects of the challenges facing our society, drawing on High Road Strategies’ prior research and analysis on the intersection of economic, energy and climate, and workforce policy issues. Specifically, the articles—and the High Road Strategies blog—will focus on three themes:

Upcoming issues of this newsletter will feature articles that explore high road approaches to different aspects of the challenges facing our society, drawing on High Road Strategies’ prior research and analysis on the intersection of economic, energy and climate, and workforce policy issues. Specifically, the articles—and the High Road Strategies blog—will focus on three themes:

Below, we summarize several of the topics we plan to cover in the articles associated with each theme.

Back to Top Articles on this theme focus on the nexus between climate change, energy, and economic growth and development. The articles examine economic risks and opportunities associated with policies to curtail carbon emissions, especially in the manufacturing, electric power, construction and extraction sectors. They also explore strategies to achieve both sustainable environmental (i.e., carbon emissions reduction) and economic goals.

Articles on this theme focus on the nexus between climate change, energy, and economic growth and development. The articles examine economic risks and opportunities associated with policies to curtail carbon emissions, especially in the manufacturing, electric power, construction and extraction sectors. They also explore strategies to achieve both sustainable environmental (i.e., carbon emissions reduction) and economic goals.

The premier article will focus on the debate over climate change reignited by the proposed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) carbon standards. Scientists and environmentalists have intensified their warnings about global warming, calling for dramatic cuts in the use of carbon fuels. The Obama administration has responded with the EPA regulations, and recently, an even more far-reaching Clean Power Plan. Conversely, climate policy opponents, especially in the fossil fuel sector, claim that carbon regulations will harm the economy. Recognizing how polarized this debate has become, our article starts from a different premise: our economy is not “addicted” to fossil fuels; instead, their use is deeply ingrained in our society’s industrial DNA. Hence, we argue, successful “high road” approaches need to start with realistic assessments of the possible economic risks and costs of climate policies, identify measures for mitigating these impacts, and promote opportunities that support workers, businesses, and communities in the transition to a clean energy economy.

Other subjects covered in future issues might include:

Back to Top

Taking the High Road also features articles on the revitalization and growth of a globally competitive manufacturing sector in the United States. America’s manufacturing base has greatly eroded since the late 1970s, and has seen a precipitous decline since 2000—over 5 million jobs and about 60,000 facilities lost, while the manufacturing prowess of major foreign trade competitors (e.g., China, Germany, Japan, Brazil, etc.) has grown. There has been a robust debate about the causes of this decline, whether revitalizing manufacturing even matters to the well-being of our economy (we believe it does!), and the best strategies and policies needed to restore America’s manufacturing strength and global competitiveness. Future articles will take a fresh look at these issues drawing on recent research, publications and real-world examples.

Taking the High Road also features articles on the revitalization and growth of a globally competitive manufacturing sector in the United States. America’s manufacturing base has greatly eroded since the late 1970s, and has seen a precipitous decline since 2000—over 5 million jobs and about 60,000 facilities lost, while the manufacturing prowess of major foreign trade competitors (e.g., China, Germany, Japan, Brazil, etc.) has grown. There has been a robust debate about the causes of this decline, whether revitalizing manufacturing even matters to the well-being of our economy (we believe it does!), and the best strategies and policies needed to restore America’s manufacturing strength and global competitiveness. Future articles will take a fresh look at these issues drawing on recent research, publications and real-world examples.

The first article on this theme will begin with an updated assessment of the U.S. manufacturing competitiveness challenge. We will review the erosion of U.S. manufacturing capacity and dramatic of loss plants and jobs—along with knowledge and skills—across the manufacturing industry spectrum, especially since 2000. We also will examine competing explanations for the causes of this decline, especially trade and tax policies and technological change. There is growing optimism about a manufacturing revival fueled by the apparent reshoring of some manufacturing production. But it is not obvious that it will be sufficient for restoring U.S. manufacturing capacity, without a robust and comprehensive national industrial competitiveness strategy. The article will discuss key elements of such a strategy (e.g., trade, R&D investment, workforce, cluster, tax, and “demand pull” investments (e.g., infrastructure, clean energy, next generation manufacturing, etc.)). Comparisons with major manufacturing nations (Germany, China, Japan) also will be made.

Other subjects covered in future articles may include:

Back to Top

In these articles we examine America’s workforce readiness challenge in the coming decades. A highly trained and educated—and well-paid—skilled workforce is considered vital to maintaining U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness. It is also important to support the growth of a strong middle class, which is critical both to create the human capital essential for economic growth and reduce economic inequality. Many policymakers and business leaders are concerned about the readiness of the nation’s workforce education and training system to address perceived skill shortages in major industrial sectors, including manufacturing, construction, energy, and high-tech, and their supply chains. At the same time, there are serious questions about the adequacy of America’s education and training systems to enable workers across the income spectrum to obtain the knowledge and skills they need to find good jobs in today’s and tomorrow’s economy.

In these articles we examine America’s workforce readiness challenge in the coming decades. A highly trained and educated—and well-paid—skilled workforce is considered vital to maintaining U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness. It is also important to support the growth of a strong middle class, which is critical both to create the human capital essential for economic growth and reduce economic inequality. Many policymakers and business leaders are concerned about the readiness of the nation’s workforce education and training system to address perceived skill shortages in major industrial sectors, including manufacturing, construction, energy, and high-tech, and their supply chains. At the same time, there are serious questions about the adequacy of America’s education and training systems to enable workers across the income spectrum to obtain the knowledge and skills they need to find good jobs in today’s and tomorrow’s economy.

The first article featured here will examine the concerns business leaders and policymakers have about perceived skill shortages in major industrial sectors, especially manufacturing, construction, energy, and high-tech industries. There is much debate and many new studies about whether the quality and quantity of the workforce is adequate for meeting the competitiveness needs of key industries; the national mismatch between available jobs and workers with required skills; whether the workforce has the new, higher skills demanded by rapid technology development; and the impacts of demographic shifts. There is a corresponding debate over strategies to improve the readiness of the national workforce education and training systems to meet the challenge. In this article, we will explore the nature, extent and factors underlying the actual skill shortages in U.S. industries, and evaluate the adequacy of the U.S. workforce education and training system to meet America’s workforce challenges.

Other articles on workforce issues may include:

Back to Top

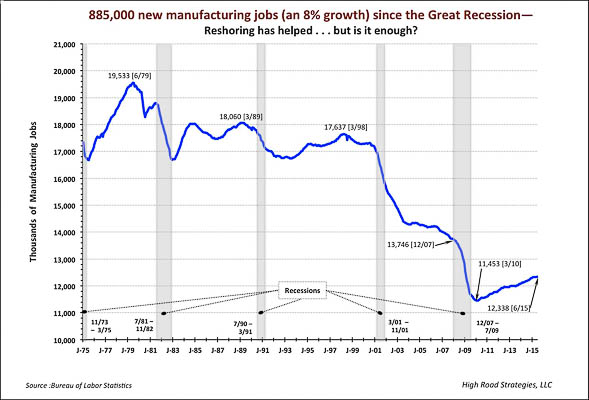

This section presents interesting and important trends and numbers, which are especially relevant to the themes explored in the articles, and the work of High Road Strategies. For example, the chart tracks U.S. manufacturing employment from 1975 to the present, showing in particular the sharp decline in manufacturing jobs since 2000, exacerbated by the Great Recession in 2007-2009.

This section presents interesting and important trends and numbers, which are especially relevant to the themes explored in the articles, and the work of High Road Strategies. For example, the chart tracks U.S. manufacturing employment from 1975 to the present, showing in particular the sharp decline in manufacturing jobs since 2000, exacerbated by the Great Recession in 2007-2009.

It also illustrates a respectable but modest net increase of 885,000—an 8 percent growth—in manufacturing jobs after bottoming out in March 2010. This gain in large part reflects the economy’s recovery, which in turn, can be partly attributed to Obama’s stimulus package. However, a portion of these gains is likely the result of “reshoring,” of some manufacturing capacity and jobs back to the United States, much of which was offshored in earlier years. The reasons for this movement are complex (higher transportation costs, rising foreign labor and other costs, an improved U.S. business environment). While an encouraging trend, it is not certain whether it will be sufficient to return U.S. manufacturing back to former its levels.

Back to Top In this section, we present brief reviews of important books, reports, articles, and other publications relevant to the newsletter’s principal themes—(the energy-economic nexus; manufacturing competitiveness; workforce readiness)—and the High Road Strategies approach, which readers of this newsletter might find interesting. For example, books we are considering for review in the next and subsequent issues include:

In this section, we present brief reviews of important books, reports, articles, and other publications relevant to the newsletter’s principal themes—(the energy-economic nexus; manufacturing competitiveness; workforce readiness)—and the High Road Strategies approach, which readers of this newsletter might find interesting. For example, books we are considering for review in the next and subsequent issues include:

We also plan reviews of notable reports and whitepapers from government, NGOs, think-tanks and other organizations. These may include:

Back to Top

In this section, we provide brief updates on some of our latest work and activities.

New Reports by High Road Strategies: In June 2015, two reports by High Road Strategies were publicly released. Details about these studies can be found on our website:

Newsletter Launch: In August,we launched this introduction to our new quarterly newsletter, Taking the High Road, on sustainable economic, energy and workforce issues. Look for the first full newsletter in your email inbox, in October 2015!

Back to Top